Between 1956 and 1958 Salvatore Emblema had the opportunity to meet and get to know Mark Rothko, finding himself in front of his artworks, admirable caskets of luminescent mysticism. That encounter is to be considered the catalyst that accelerated the chemical reaction from which Emblema's most strongly connoted painting was generated, which for several years already, had identified its own privileged field of reflection in chromatic vibration, in the search for a light osmotic to the material itself and in the peremptory impact of the centralized aniconic image. Emblema derives the necessary fuse for a creative explosion, however, quite different and distinct. Focused once and for all on his own deepest artistic personality, Emblema needed nothing more than solitary concentration, pursued consistently for many years in the isolation of his studio in Terzigno, below the slopes of Vesuvius. As Palma Bucarelli rightly pointed out in 1979, Emblema had found that “the chromatic radiation by which, in Rothko, color forms a spatial nebula around itself, ends up destroying not only the surface, but also what could be called the surface structure of the painting”, thus arriving at the painting-object that “leads to operating directly, manually, on the physical reality of the canvas and the frame.”

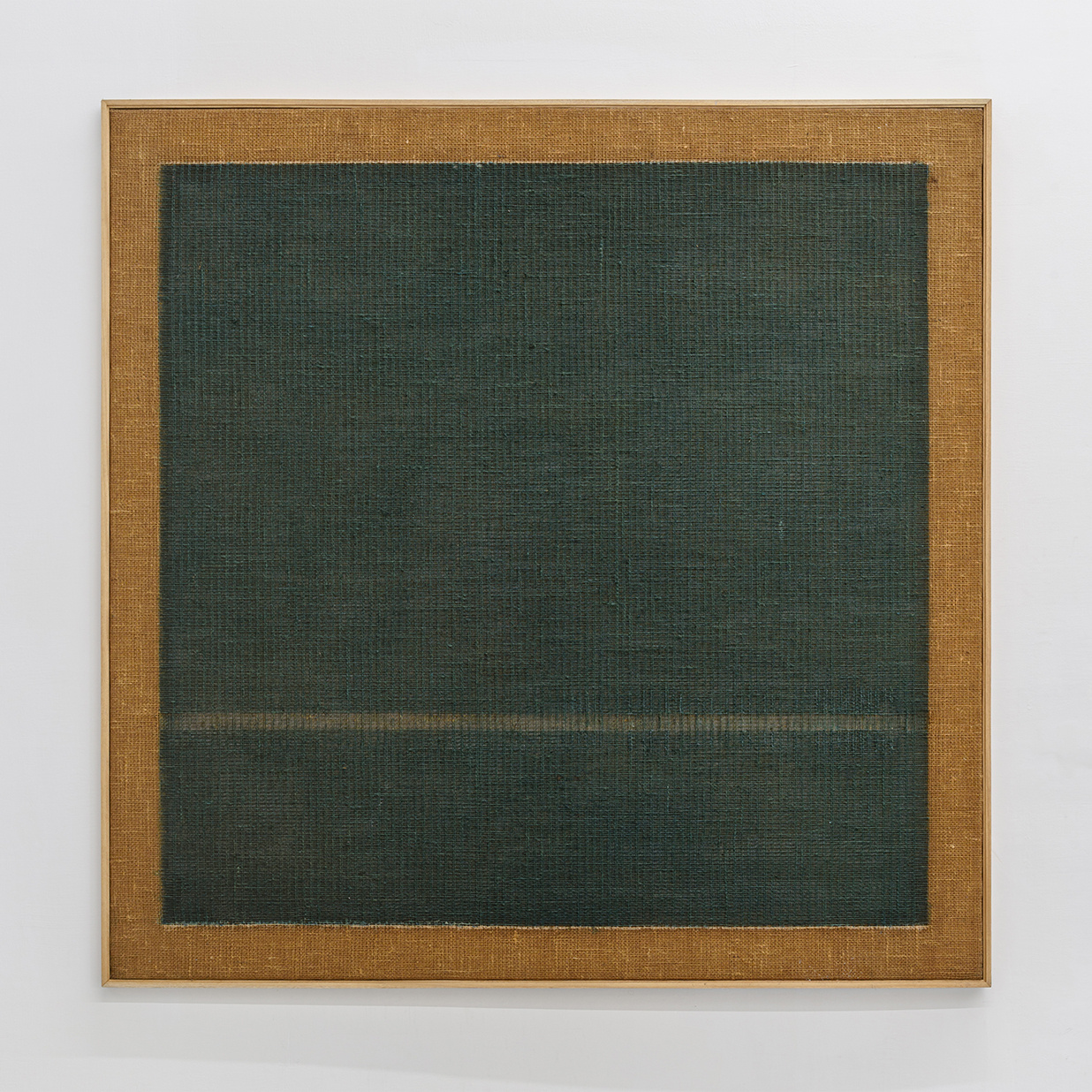

In Emblema's research there are nature in motion (the dramatic dynamism of the earthquake) and the lava soil of Vesuvius. Moving to another plane, Emblema has focused more on the relationship between canvas, frame and color, in line with that analytical and conceptual temperament of abstract painting that took hold in the 1970s. Here then is that the luminous vibration of his paintings, always calm, deep and chromatically attentive, springs from the unitary, structural and osmotic integration between color and jute canvas, often thinned out through the elimination of some threads. In this way the artist removes, reduces, synthesizes, while still remaining faithful to the painting.

In doing so, the artwork, because of the transparency of the support, becomes relativized and affected by the environment in which it is placed. As Bucarelli again noted, “Emblema's 'thinned out' painting tends to identify with the wall, the room, the landscape: to be, in short, a test that, in contact with reality, reacts to the extent to which that reality is experienced and thought about, that is, naturalized and spatialized.”

The instinctively conceptual soul of Emblema's research, also clearly evident in the fine selection of these works, finds confirmation in that sort of mental detachment suggested by the framing of the rough canvas “frame” within which the painted action takes place. Somehow, for the artist, the painting is a filter, a screen, a membrane of air, light and shadows that must be inserted into everyday reality, with which he establishes a perhaps difficult and always problematic dialogue.

Of great importance in Emblema's research is precisely the manual and artisanal intervention. “Emblema takes to the extreme edge the analysis of painting even as a craftsman, as if to show that, in order to save itself from the general collapse of values, it must return to its origin as modest but deeply cognitive manual labor.” This aspect, and more, was also addressed by Giulio Carlo Argan who argued “the painting is always a screen, but no longer a screen of projection. It interrupts with its plane the unity of space and, by imposing a pause and a moment of objectification, the continuity of time. Not withstanding it, Fontana solved the problem as a fencer by pointing and cutting. Emblema tackles it with the patience and humility of a craftsman by unthreading the canvas and thinning the surface, simultaneously burdening his hand on the rough carpentry of the frame. [...] By unthreading the canvas, the screen becomes a filter and allows the painter, as he phenomenizes the light, to dose its effusion and vibration with the delicate arpeggio of the threads.” Argan thus arrives at the definition of “detessitura.”

Starting in the very early 1980s, the Terzigno artist began to monumentalize gestural sign presences and color fields, to give them a more sensual charisma, loosening the ascetic linguistic analysis of the previous decade. In the works of the last two decades, one almost seems to glimpse, at times, outlines of landscapes and cultivated fields, glimpses of skies, silhouettes of clouds or leaves, flights of swallows or the germination of seeds and the micro earth tremor of natural life hidden in the rural and woodland humus. Thus that telluric soul identifiable with the germinal process of nature is accentuated. Emblema had somehow returned to a contemplation of the external world filtered, however, by the inflexible rule of a painting conceived as an “adventure into the unknown.”

Read less

Between 1956 and 1958 Salvatore Emblema had the opportunity to meet and get to know Mark Rothko, finding himself in front of his artworks, admirable caskets of luminescent mysticism. That encounter is to be considered the catalyst that accelerated the chemical reaction from which Emblema's most strongly connoted painting was generated, which for several years already, had identified its own privileged field of reflection in chromatic vibration, in the search for a light osmotic to the material itself and in the peremptory impact of the centralized aniconic image. Emblema derives the necessary fuse for a creative explosion, however, quite different and distinct. Focused once and for all on his own deepest artistic personality, Emblema needed nothing more than solitary concentration, pursued consistently for many years in the isolation of his studio in Terzigno, below the slopes of Vesuvius. As Palma Bucarelli rightly pointed out in 1979, Emblema had found that “the chromatic...

Read more